At the end of last year, the Eurosystem Research Network on Cash (EURECA) held a workshop at the European Central Bank (ECB) to consider the latest currency research.

The agenda gives an immediate insight into the priority areas of interest to central banks:

Beyond the ECB and its National central Banks (NCBs), speakers came from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Bank for International Settlement, the Bank of Canada, Bank of Japan, the Swiss National Bank and a number of academics.

EURECA was launched in July 2017 to pool research efforts and promote studies on cash-related topics. The network includes economists and cash experts from the ECB and Eurosystem NCBs, along with external collaborators working on cash-related topics. EURECA primarily takes a data, quantitative and scientific approach to addressing key topics to provide evidence for informing policy decisions.

While the presentations were frequently technical and the discussions more about the modelling than the conclusions, some important points were made.

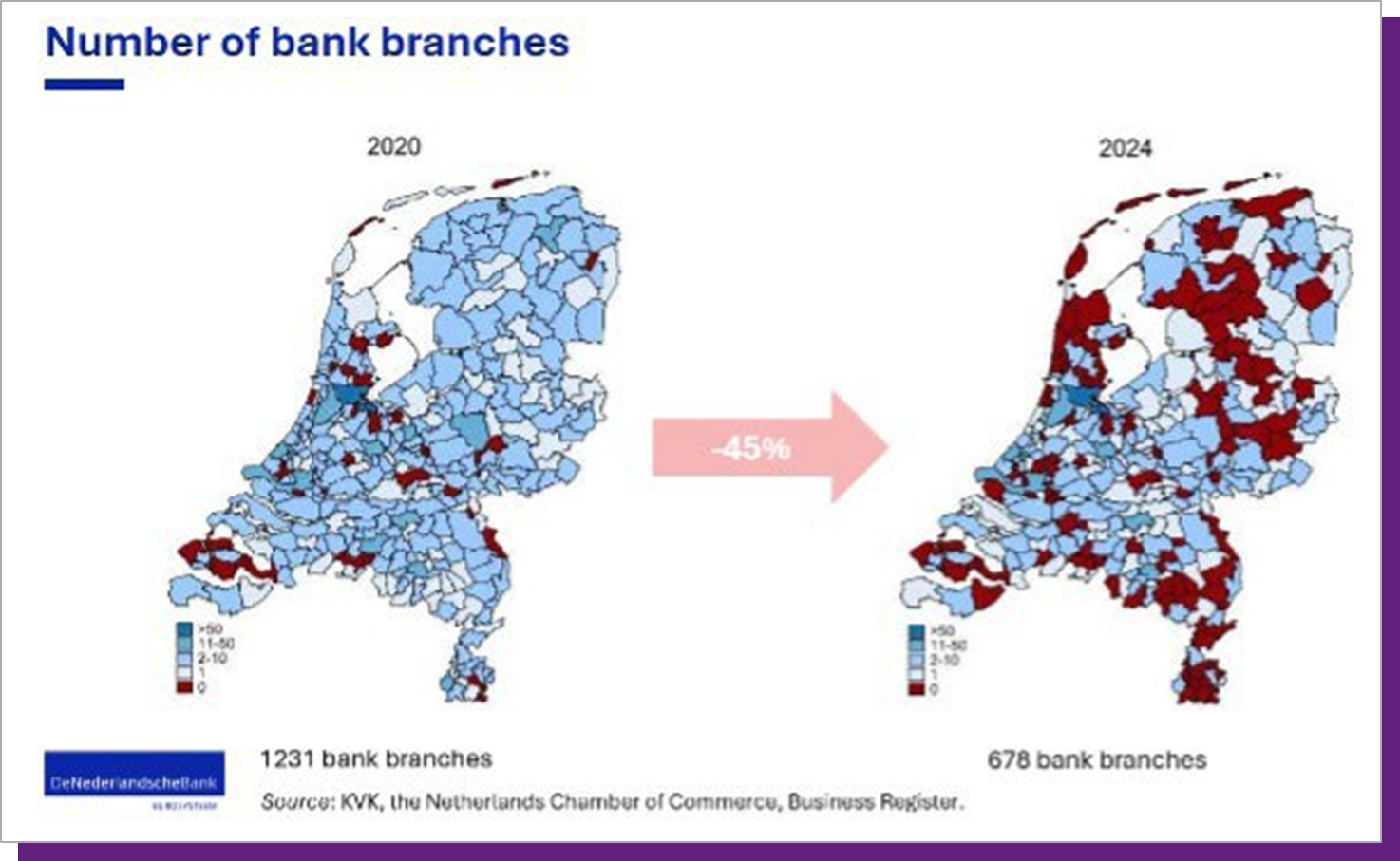

In this paper the Dutch National Bank (DNB) explored the relationship between the presence of branches and consumer trust in the payment system. In 2013 there had been 2,063 branches in the Netherlands. By 2025 that number had fallen to 602. In 2013 there were four municipalities without a branch, today there are 148 out of 342. The average number of branches per municipality has fallen from six to 1.8.

Despite that, trust in the payment system and in people’s own banks hardly changed between 2021 and 2024, increasing by 0.01/5 and falling by 0.05/5 respectively.

The reasons are not clear, but the availability of effective alternatives and that the impact of closures only affects very small specific groups may play a role. Even where there are no branches, trust was not significantly affected.

The ECB looked carefully at the role of age in determining cash usage. Perhaps surprisingly, it found that young adults, those between 17 and 27 years old, use cash about the same as the average for all age groups. They are also more likely to keep cash at home than other age groups.

The perceived importance of cash has increased since 2019.

The Bank of Canada asked a question in their 2023 Methods of Payment survey about whether people made a specific trip to withdraw cash from an ATM or combined it with another activity. 32% of people did not combine going to an ATM with another activity.

When this information was used in cost of cash modelling, it reduced the travel cost element by 25%.

The four key findings from the ECBs study of the use of cash in crises over the last 25 years were:

The OECD reported that the drivers of payment digitalisation are cost efficiency, the authorities using regulatory and security powers to tackle policy goals such as limiting illegal payments, increasing financial inclusion, and the effects of COVID-19.

However, declining access to cash highlights concerns about financial consumer protection. A paper by van der Cruijsen and Reijerink in 2023 found that if 28% of the population cannot do without cash, 45% of people with low digital literacy, 36% of those with disabilities and 35% of those in financial difficulty needed cash. Consumer vulnerability is real.

People with low digital literacy are also those with a higher risk of being scammed or defrauded when using digital payments. Finally, there is, of course, the need for an effective store of value mechanism.

The result of these concerns are initiatives to develop national policies or strategies to safeguard acceptance and availability of cash.

The Bundesbank has experimented using mystery shoppers to understand whether cash acceptance is a problem. 2,060 test shops were carried out in retail stores, and 30 tests were carried out on buses and 30 with public authority payments.

While the results show that in 99% of cases it was possible to pay with cash, the novelty here is understanding how to do mystery shopping.

The IMF explained modelling to show what happens when a new payment method is introduced into an economy. This work is important because every payment method has its own specific functions which it does better than the alternatives. Once a payment method disappears, it is almost certainly gone for good.

The methodology was applied here to the introduction of a CBDC, with three findings.

1.A new currency succeeds only if it is launched on a sufficiently large scale

2.A new currency launched as a ‘complement’ to existing currencies is not successful

3.A new currency can lead to the extinction of other currencies even when the new currency is not successful.

Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB– Austria’s central bank) has carried out research to understand the appetite for a digital euro.

The research started with some assumptions – there would be no interest paid on digital euro accounts, it would have only a limited store of value function, and merchant acceptance would be mandatory.

For those researched, 18.9% said they would defy the digital euro (defiers), never take it (5%), rarely use it (13.3%), sometimes use it (31.8%) and always use it (31%).

The characteristics tested were:

The research found that the top three attributes that matter were security against full loss, against partial loss and gaining an incentive of €10 per month. Having said that, 30% said privacy was more important than monetary savings.

If the digital euro had no incentives, full protection, limited privacy, worked offline and was available as a card, 45% was seen as a realistic roll out level of adoption.

The key to adoption were people with a high risk tolerance, who trust the central bank, have unmet payment needs and are younger.

A paper by the Study Center Gerzensee, University of St Gallen and the Swiss National Bank looked at the social influence in youth payment behaviour.

It found that changes in payment behaviour are not driven by changes in consumption patterns. What did make a difference was receiving electronic transfers from parents.This is associated with large decreases in cash use.

Engaging in person-to-person payments had no impact, nor did indirect parental or peer effects. It appears that preferences and beliefs are independent of social influences.

The DNB investigated the role of rebates in card networks. Existing literature focuses on the interchange fee based on card usage. Interchange fees are now regulated in many jurisdictions.

The purpose of this paper was to explore a new model to analyse incentives and the impact of rebates. Give that Visa and Mastercard have net profit margins of 45-55% and spend 25-30% of their gross revenues on rebates in order to steer card adoption, understanding this is important.

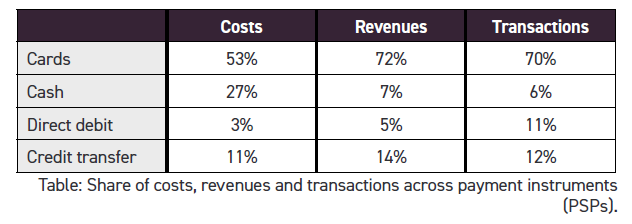

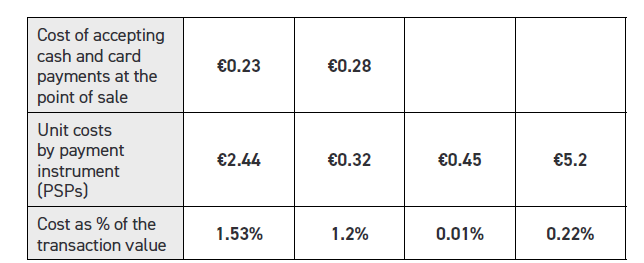

This was a useful look at the relative cost of cash.

The imbalance of the cost of cash compared with revenues, particularly when compared with the figures for cards, explains why cash is seen as expensive. The cost of a cash payment, €0.23, is less than that of a card payment, €0.28, but when expressed as a percentage of the transaction value that is reversed. Cash is 1.05% of the value, a card is 0.57%.

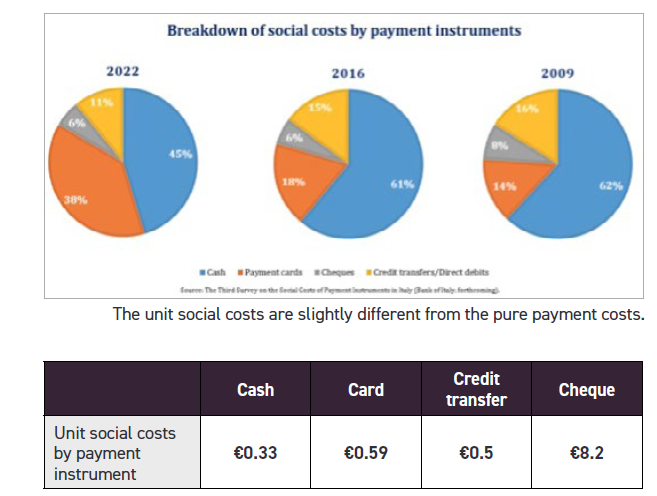

The paper then looks at the societal costs by payment instrument.

Not every presentation was covered and only a few highlights have been reported. There is high quality work here of great interest in those involved in cash and the future of cash.

A few key takeaways are: