In September Franz Seitz and Gerhard Rösl published a paper laying out the challenges and risks faced by cash in countries moving to being less cash societies 1. It is a tour de force providing both facts and arguments about what can be done. It provides the context and the arguments for the future of cash discussions heard at every conference this autumn – ATMIA, Coin, Retail Branch Transformation, High Security Print.

The paper argues that cash continues to have a critical role both generally and, in particular, at a time of crisis.

Declines in cash usage are often the result of supply side actions, many of which originate from government or central bank. Given that central banks take the ‘profits’ of cash while placing many of the costs on the private sector and that the role of cash has societal welfare benefits beyond its direct functions, central banks should move beyond being neutral to support cash.

For cash to fulfil its role as a stabiliser at a time of crisis, it needs a well-functioning cash cycle, one that is resilient. Reducing transactional cash usage makes this harder to achieve.

To be a good store of value, ie. providing highly liquid assets, useful and usable at a time of crisis, cash needs to be used as a means of payment. Different types of crises determine which denominations are required. Payment system outages require transactional notes. Political and financial crisis damage confidence driving demand for non-transactional notes. Whichever is needed, for cash to work in a crisis, it must work in normal times. The habits, infrastructure, acceptance, access, availability, and affordability of cash must be safely and reliably in place.

The data shows that even with a period of high interest rates and high inflation, demand for cash overall remains high.

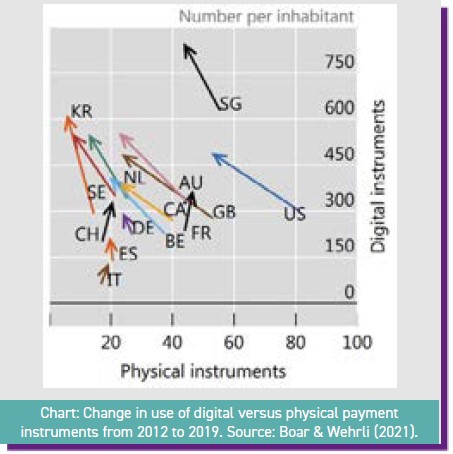

However, cash usage at the point of sale (POS) is falling in many areas – in the UK it fell from 55% in 2011 to 15% in 2021, in China it fell from 22% in 2017 to 8% in 2022.

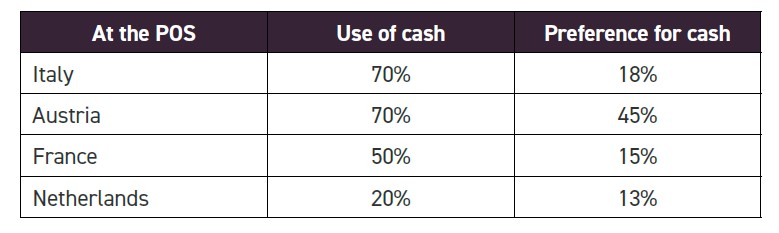

The correlation between the preference for cash and the actual use of cash, as revealed in surveys, is under 50%. ECB data below shows how the ‘say-do’ gap can work both ways.

Either people are overstating their preference for cash, or there is a supply problem.

An ECB survey asked, ‘if you were offered various payment methods in a shop, which would you use?’. In 2016, the Europe wide answer was 32%, dropping to 27% in 2019 and again in 2022 to 22%. The top three reasons were so as not to have to carry cash, speed, and convenience.

Another possible option is incentives to pay with non-cash means, including collecting points. In addition to the commercial incentives, the paper gives details of government incentive schemes to use non-cash payments in Japan, Korea, Greece, and the Netherlands (where consumers are incentivised to use a debit card). The only country offering incentives to use cash was Austria.

Here governments and central banks have played an even more active role, usually in the name of combatting corruption, tax evasion, drug trafficking or terrorism. Examples of supply side restrictions include:

At the same time, commercial banks have been closing branches and ATMs. In Sweden, ATMs don’t issue Kr500 notes or higher (€50).

Commercial banks bear the cost of cash provision, but not the ‘profits’ that come from seigniorage. On the other hand, digital payments can be a profit centre for them. Alongside payment providers such as Visa and Mastercard for whom payments is their business, they have a direct interest in promoting digital payments and reducing cash payments.

Perhaps it is no wonder that cash is struggling in many countries.

In addition, as the ECB Executive Board director Cipollone said this year, ‘the decline in the use of banknotes also risks reducing their attractiveness as a store of value in the long term’ and we have now seen, for the first time, there has been a fall in euro banknotes in circulation.

Across Europe in particular, we are now seeing legislative action to ensure access to cash – Ireland, the UK, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Finland, and Lithuania. The European Commission is also debating regulation. Australia, New Zealand and the US have also taken steps. Sometimes this is for access only, but acceptance is also on the agenda.

The importance of affordability

In a study of the cost of cash across the US, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, only in the US was cash cheaper than digital payments. The actual cost of digital payments is famously hard to know, which doesn’t help. Of these countries, all are less cash, other than the US, and so cash volumes have fallen.

The challenge is that cash lacks a viable business model in a less cash scenario with realistic interchange fees (and reverse interchange fees – where you withdraw cash other than from the bank that holds your account).

In the UK, the Payment Choice Alliance has found that interchange fees are 40% lower than in 2004 but non-bank ATMs are now delivering 80% more cash per ATM withdrawal. Is it a coincidence that between 2022 and 2024 the number of free to use ATMs fell 10%, and the number of withdrawals also fell 10% while the value withdrawn did not change?

The paper quotes the ‘costs by cause’ principle where suppliers should receive profits but also bear costs of their products in order to ensure maximum efficiency in the market. While central banks receive the ‘profits’ of cash, the private sector bears most of the costs. Is it unreasonable, therefore, that the costs of the provision of cash services should be covered by those profits?

Conclusions and recommendations

Central banks need to take active steps early to avoid cash usage dipping below a point where the cash infrastructure is not viable, and cash cannot deliver either resilience or broader societal benefits.

1 - Resilience and the Cash Infrastructure: The Role of Access, Acceptance, Availability, and Affordability. Gerhard Rösl, Franz Seitz. Weidener Diskussionspapiere Nr. 93, September 2024.