The Future of Cash conference had a special seminar dedicated to the cost of payments with presentations by the US Federal Reserve, Swiss National Bank (SNB), Bundesbank, European Central Bank (ECB) and Tobias Truetsch from the University of St Gallen.

Franz Seitz, from the Weiden Technical University of Applied Sciences and moderator of the seminar, started by observing how little research there is into the cost of payments. Comparative studies are even rarer, with the Santiago Carbo-Valverde and Francisco Rodriguez- Fernandez 2019 paper, a study across 51 countries, being the exception. The complexity and cost of doing these studies appears to be the problem.

The SNB’s paper included a question to companies about why they accepted cash payments. The answer was that cash was significantly better than the alternatives in terms of cost and reliability compared with non-cash payments, but worse in terms of the risk of theft. In addition, they had to accept cash because customers needed and wanted to pay in cash.

It would be interesting to understand what was meant by ‘reliability’. Consumer behaviour can change and costs can change, but if reliability were to mean assured payment or resilience against software or power failures, then this is a powerful positive for cash that is likely to remain.

It would be interesting, as well, to ask businesses the same questions for non- cash payments, particularly around the risks of theft and crime.

The SNB asked businesses how they accessed cash and one part of the answer said cash in transit (CIT) services were hardly used. Businesses used their banks, post office and customer cash in/cash outflows to manage their cash.

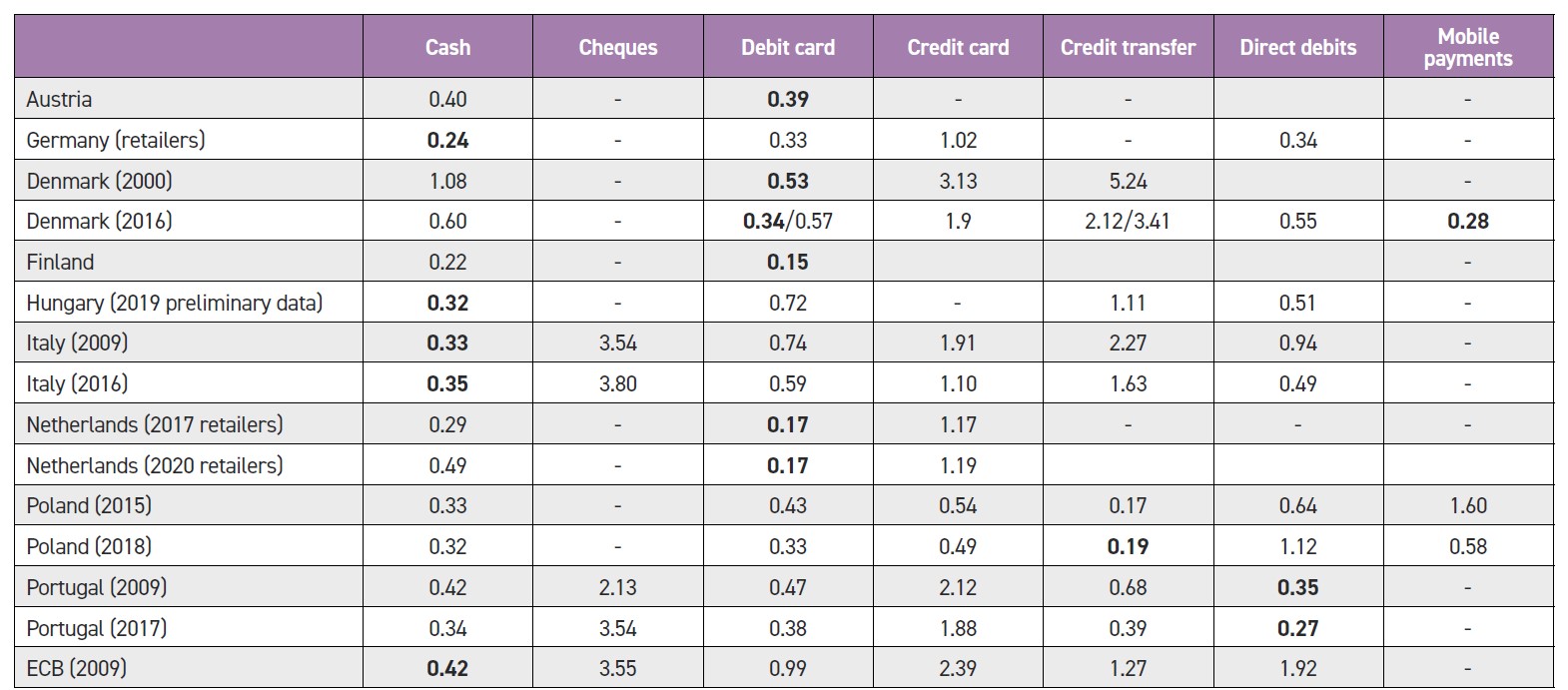

The ECB paper looked at nine cost of payment studies conducted across Europe in recent years. They found that the payment environment was changing, driven by three elements – digitisation, regulatory change (Payment Services Directive 2, for example) and changing payment habits.

The ECB defined societal cost as the cost of providing payment services to society and coming from the resource costs incurred by all parties along the supply chain. This is in contrast to private cost which are the costs incurred by individual stakeholders. If you regard cash as a public utility to be preserved, one might focus on private cost since this drives behaviour. A central bank though, has an obligation to consider the societal cost.

One challenge here is that powerful entities in the payment landscape have the market ability to shape the behaviour of consumers, merchants and even banks. The societal cost, particularly in terms of consumer behaviour, does not just exist.

Such ideas are hard to research and understand. The Bundesbank, for example, found that card costs are the biggest cost element for non-cash payments.

When the work of the nine studies was compared, in only one country was cash the most expensive means of payment. This was Finland, where cash volumes are low. In three countries cash was always the lowest cost means (Germany, Italy and Hungary) and overall cash was the lowest cost.

The work shows that when cash volumes are ‘high’, cash has the lowest societal impact per transaction. This is because fixed costs for debit cards are high and so as their volumes rise, they become less expensive. This raises questions about whether central banks should support societal good by acting to maintain cash volumes.

Tobias Truetsch reported on research that showed when the cost of a payment was made visible to consumers, with the price the same for all, then people’s behaviour changed. The change was statistically significant with people opting to use lower cost payment means.

This supports the case for requiring the cost of payments to be visible to allow true consumer choice.

The presenters were reporting on their studies, but to the audience questions were raised about the ability of commercial players to manipulate costs to further their own interests, about whether central banks could and should actively support cash volumes, whether requiring the cost of payments to be shown to consumers and whether the ‘reliability’ of cash is a fundamental strength.