With Sweden’s decline in cash usage, Sveriges Riksbank is less involved in the payment system and is, therefore, less able to meet the requirement placed on it to promote a safe and efficient payment system. As a result, the Riksbank is conducting a pilot project to create a token-based Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) known as the e-krona.

The Riksbank has now issued its report on the first phase of the project and has extended it for a further year to carry out more investigations.

The approach being taken does not imply the Riksbank will introduce an e-krona, nor that it would be based on this solution should that decision be taken.

The project, undertaken with the support of Accenture, is to allow the Riksbank to analyse policy relating to a CBDC, along with technical, security and legal issues. It uses a distributed network on blockchain where the e-krona token is created only by the Riksbank. Each e-krona is uniquely identifiable, has a unique value, although this can vary, and is guaranteed by the state.

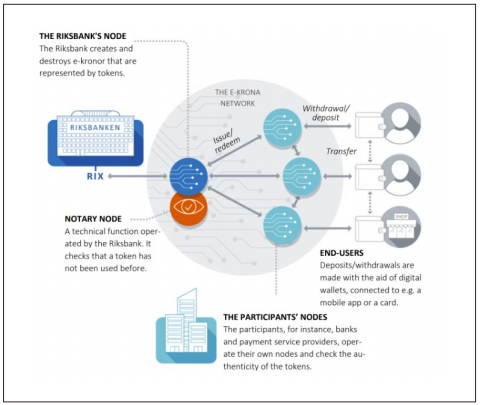

Only the Riksbank can create or destroy an e-krona. The Riksbank issues e-kronor to distributors, known as ‘participants’, who are registered, regulated financial institutions or payment service providers.

A participant runs a ‘node’ on the system. Through their node they request, or return, e-kronor from the Riksbank through the RIX system and their account at the Riksbank is debited or credited accordingly. This is the usual interbank settlement system in Sweden. The participant holds the e-krona in their secure ‘vault’ as they would cash.

When an end-user wants e-kronor, they exchange holdings in their payment account for the e-kronor and hold these in their digital wallets. The digital wallet is connected to a payment instrument such as a phone or card. The reverse process applies should they wish to return e-kronor.

An e-krona is only used once. It moves from a state referred to as being ‘unconsumed’ to having been ‘consumed’. When it is ‘consumed’, given to another person or organisation, that e-krona forms a new value, a new ‘unconsumed’ identify. For example, if a SEK 100 e-krona is used to settle a SEK 60 bill, new e-kronor worth SEK 60 and SEK 40 are created. The new e-kronor carry their history with them from when they were issued by the Riksbank through every stage and transaction of their existence.

Before the transaction takes place, the entire history of the e-krona is checked by something called the ‘notary node’ back at the Riksbank. In a sense this is similar to when a banknote is checked to see if it is genuine. The notary node is checking that that e-krona has not been consumed before.

Unlike cash, for an e-krona to work, the individual must have a digital wallet connected to a payment instrument and must be able to communicate back to the notary node.

There are two parts to an e-krona, the token and the private key that locks/unlocks it. These can exist in different places, but you need both together to use an e-krona. The phase 1 pilot has only tested one option to date, alternative B.

The most cash-like alternative is alternative A. With the token, key and transaction history all stored on the payment instrument, the user has complete control. If the payment instrument is lost, it is hard to get the e-kronor back. In addition, normal banking functions, such as direct debits, won’t work.

In alternative B, the tokens, and their transaction history, are stored on the network at the participant’s node. The e-krona is held in a digital safe separate from other e-kroner. The key is stored on the payment instrument, giving the user exclusive right to execute transactions.

In the final option, alternative C, tokens, and their transaction history, and the private key are stored in the network at the participant’s node separately from e-kronor belonging to other people. This is similar to an account balance linked with a payment instrument. It gives, therefore, the option for similar functionality to a bank account such as direct debits.

The underlying technology used in the pilot has been the R3 Corda platform, a decentralised private network on to which participants are admitted and allowed.

The network is parallel to existing payment systems but does not use them, providing the possibility of additional resilience should the existing payment systems fail. The only cross over is at the RIX system for settlement.

The Riksbank compared the e-krona to cash, account balances, electronic money and cryptocurrency to establish whether it fits within existing laws and regulations or whether new legislation will be necessary.

Its conclusion was that it is not the same as an account balance because it is not a claim on a private actor, but has its own identity stored in a ‘safe’.

Electronic money is regulated in law, allowing institutions to issue a means of payment, but they do not have the right to accept deposits. The means of payment are pre-paid to the institution and the institution may not use the means received for their own commercial purposes. The electronic money cannot bear interest. E-krona is significantly different from electronic money.

E-kronor shares many of the attributes of cash. They are uniquely identifiable, are only created by the Riksbank and the end-user has exclusive right to use them, through the private key in the case of e-krona. The need for technical aids, access to communications and participants in order to be able to make a transaction means that e-krona is not cash but a new means of payment.

The Riksbank concluded that new legislation is needed. It also desirable since it will allow the law to fit the character of the e-krona fully.

E-kronor will need to comply with legislation such as Anti-Money Laundering regulations. The distribution model used by the Riksbank means that this responsibility will lie with the participants. Anonymity will be limited as a result.

Although the Riksbank has learnt and established a great deal, it has significant outstanding questions.

Scale: The function of the notary node is to be confident that the e-krona has not already been consumed, requiring interrogation of all of the sub-divisions of the original e-krona since it was created. This is information intensive and so whether it will work at scale needs investigating.

Traceability: Because the Riksbank e-krona pilot is based on an approach requiring the previous chain of transactions to be verified to ensure authenticity, the question of whether the information about other transactions and participants breaches either banking privacy or personal data legislation needs to be fully answered. More work is needed.

Off-line functionality: What happens if the payment instrument is stolen, broken or criminally attacked? How robust is the system and can value be recovered?

Balance cap and interest rates: An option for controlling the demand and supply of e-kronor is available by putting in place a cap on the balances that can be held on a wallet. Another way is to introduce interest rates, particularly negative interest rates. A negative interest rate is incompatible with local storage of e-krona, where exclusive control lies with the end user linked to the payment instrument (alternative A). This is more than just a technical issue but a policy and legal issue as well.

Resilience: More work is needed to understand the robustness, performance, communications, addressing of payments and possibility to settle payments. In addition, will the solution bring in new participants to the system? Will it be highly efficient? Will it be resource heavy or light?

Legal: If e-kronor are a means of payment with an independent value, the Riksbank might be able to use the same legal principles that apply to cash. If e-kronor are to have interest rates applied to them, then e-kronor is a claim, effectively a promissory note in digital form. But it cannot be both. In addition, there is a question about whether the Riksbank should, in specific cases, undertake to redeem e-kronor directly from the general public.

In the next year the five areas of research are:

Involve potential distributors as participants in the network to test how integration with their internal systems could function with the e-kronor network.

Explore the three ‘alternatives’ rather than just alternative B.

Explore the capacity for off-line payments.

Continue testing how it works for retail payments, for example working with point-of-sale and other digital payment equipment.

Analysis of the e-kronor network infrastructure.