At the recent CBDC Conference in Istanbul a number of key themes emerged. That the given focus of this event, as its name indicates, is predominantly on Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), these themes were in sharper contrast to the subsequent Digital Currency Conference in London, which had a broader remit.

While 134 countries are reported to be researching or working on CBDC projects, there is a clear sense that the ‘heat’ has gone out of this topic around retail CBDC, particularly in the Advanced Economies.

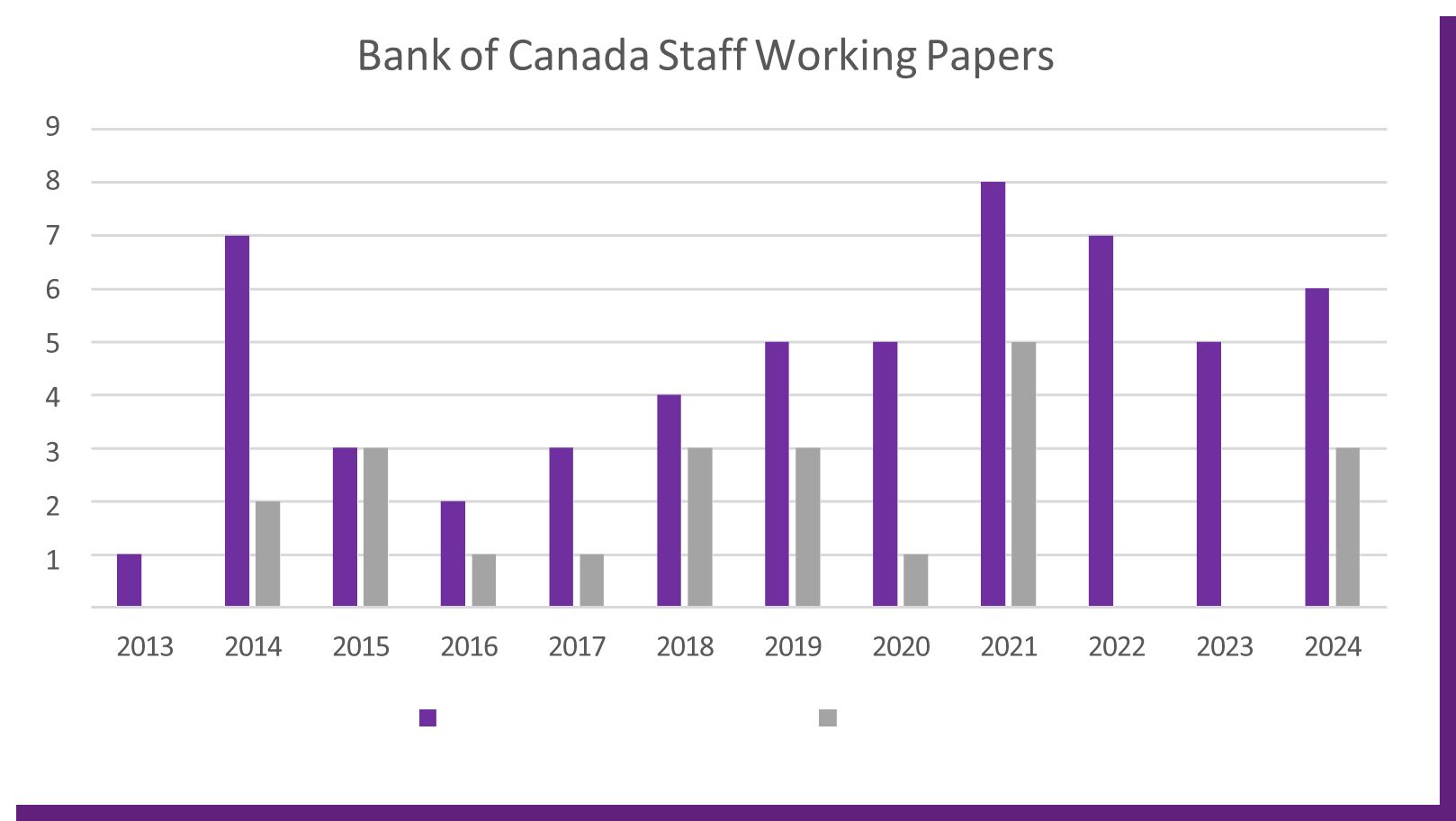

It may be that from 2017, when the Bank of Canada CBDC articles started to increase leading to a surge of interest and activity, the conversation about CBDC has become more mature and the thinking and arguments for and against it more developed.

The recent announcements by the Bank of Canada and Reserve Bank of Australia, that they don’t plan to issue a CBDC, add weight to this hypothesis, along with the politicisation of the Digital Dollar making the Federal Reserve also step back. The European Central Bank (ECB) remains active, alongside China, Russia and India.

Other than political resistance to CBDCs, central banks appear to be struggling with compelling use cases. In addition, the development of faster payments and the examples such as Pix in Brazil run by the central bank (see page 3), perhaps reduces the urgent need for CBDC and offers an alternative option.

In contrast interest remains in wholesale CBDC because they have the potential to reduce the cost, time and complexity involved in cross border payments. A more concrete use case, despite the best efforts of Swift and advocates of Stablecoins and a wide range of Digital Tokens, is driving action and activity. In this case politics, a wish to reduce the dominance of the US Dollar, is a spur to action for some.

As expected, there was considerable focus on use cases, safeguarding privacy and combatting cyber-crime. What is perhaps more interesting, is what was not discussed – trust, seigniorage, store of value, transaction fees and interest rates.

Trust: an important element of the privacy debate is the ability of central banks to put in place technical, legal and procedural protection to reassure users that a CBDC offers more privacy than commercial digital payments. What was not discussed was how central banks can persuade the population that they are at arms-length from the state and can safeguard their data. The decision of the Canadian government in 2022 to use 1934 legislation to freeze the bank accounts of the leaders of a highly disruptive truckers strike protesting against COVID restrictions will be used as evidence that even the most liberal government will use money to control behaviour.

Further, while programmable money is regarded as offering wonderful benefits, for cautious citizens the ability of the state, as in Thailand, to say you can’t spend this money outside of a given area and on certain goods and services is not automatically a positive.

Seigniorage: nobody talks about earning seigniorage on CBDC. It would be interesting to understand the accounting for the provision of CBDC both to payment service providers and account holders.

Store of value: in a highly digitised world, how does the state expect citizens to hold value?

Power and connectivity cannot be guaranteed. There is no discussion about how society will function should there be a prolonged denial of service. The Bank of England is looking at a holding limit of £10,000-£20,000. That may well suffice for most of the population, but the ECB, and others, are talking about much more modest levels, €3,000 for example. But why shouldn’t people hold significant value in a physical form? Without cash, what does the state envisage will happen?

Transaction fees: while there is much talk of an advantage of CBDC being low cost and free of charge in the same way as cash, there was no discussion of how this would be delivered. The intermediaries will surely charge fees for their services, the payment service providers who run the point-of-sale equipment and settlement system will charge fees. There may be small savings if the role of the likes of Visa and Mastercard can be reduced, but it would be good to have an analysis of what the costs will be.

Interest rates: at the Digital Currency Conference, the Bank of Israel said they are looking at paying interest on CBDC holdings in order to incentivise people to use CBDC. No other central bank mentioned this, and a number were clear that they would not.

Why central banks should issue a CBDC Despite the items that were not discussed, four clear benefits of a CBDC were given in presentations at the CBDC conference and Digital Currency Conference. The importance will differ by country of course, and there will be others, but the four are:

In that context, consider the fact that only 4% of transactions in Norway are in cash. Despite that Norway maintains cash and the required cash infrastructure. It does not stress about doing this.

Given that the mere existence of the CBDC delivers those policy benefits and that, unlike commercial organisations, central banks can afford to take a long view, and the costs will be met by CBDC seigniorage income rather than directly from tax revenue, why are central banks stressing about if a CBDC is introduced and if it has low usage levels?

Ultimately politicians will decide if CBDC is introduced, but perhaps central banks should be less obsessed about uptake levels.