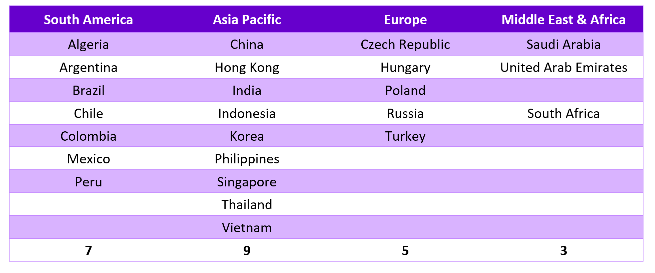

In preparation for a meeting of emerging market economy (EME) Deputy Governors organised by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the BIS surveyed 26 central banks and received papers relating to their Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) work from 24 – see the end of this summary for details. The BIS has issued a paper 1 summarising where the seven South American, nine Asian-Pacific, five European and three Middle Eastern and African are on CBDCs.

No country is the same and the data showed a wide range of views and status in preparation and thinking about CBDCs. For example while China is almost ready to launch a CBDC and Hong Kong, Saudia Arabia, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates are ready to carry out pilot or proof of concept work, Poland and Singapore do not see the need for one.

The 26 central banks gave 65 reasons for introducing a CBDC across nine motivators and the motivations were not mutually exclusive. The top four were a step higher than the fifth motivator, which only five central banks cited as a motivation. Interestingly reducing cash distribution costs came seventh with only three banks supporting it, although one of those was India.

Cash alternative: The need for a cash-lite means of payment was because of evidence of reduced cash usage and increases in private digital payment services. Central banks felt that the commercial bank monopoly of payments has gone and that cash to GDP ratios are declining in some EMEs, particularly China. A CBDC could be a marker of trust, keeping central banks as issuers of the unit of account and the anchor of the monetary system.

Financial inclusion: For almost half of the central banks financial inclusion was in the top half of their rationale for issuing a CBDC. For Peru, Mexico and South Africa it was the top reason. The papers suggested the key blocks to financial inclusion are a lack of access points, insufficient information and communication technology infrastructure, the high cost of electronic payments and an unwillingness of the private sector to serve some sectors of society. In addition, some structural challenges are financial and digital illiteracy, lack of funds and limited trust in service providers.

The structural challenges are not really addressed by the introduction of a CBDC, although mitigating actions are possible. However, the other key blocks could be addressed by well-designed CBDCs.

Increased efficiency of domestic payments: Brazil, Thailand and Russia saw this as important. There was a belief that the payment service providers (PSPs) often gain an oligopoly through their network effects which allows them to keep prices high and to hoard information. A CBDC should be able to offer a solution to both these negative effects. Some even cited the possibility of gaining a ‘late mover advantage’, ie. addressing long term problems through the new technology such as integrating the payment of utility bills into the system.

Privacy: Privacy and data protection are much thought about problems. Data is collected at many points in the payment system and so any solution will need to have common rules around data collection, storage, ownership and sharing. Systems will need to be interoperable.

The paper suggested that CBDC can be designed to separate payment services from control over the resulting data. This could allow anonymity with respect to specific parties, such as PSPs, businesses or public agencies. Like some Faster Payment Systems (FPS), CBDCs could give users control over their payments data, which they could choose to share with PSPs or third parties. It gave as an example India’s UPI scheme where data ownership and control over their credentials are addressed through application programming interfaces (APIs) that use public key cryptography. The data and privacy management challenges under CBDCs are not new.

Again, the number of risks was greater than this but the number of central banks citing the risks at the end of the list tailed off quickly.

The channels and consequences of disintermediation were also ranked with lower deposit bases, consumer deposit volatility, increased costs of funding, lower levels of bank lending and higher loan rates given as the top five.

The risk of low adoption rates is real and is already a reality in some of the countries introducing CBDCs. Considerable investment in education and incentives has been required. The paper suggests that CBDCs will need to satisfy unmet user needs if they are to be broadly accepted. It goes on to comment that FPS systems such as PIX in Brazil and UPI in India, mobile money in Kenya (M-Pesa) and Switzerland’s SWISH system already provide customers with most of the benefits identified for CBDCs. That leaves cross border payments.

The solution identified by the central banks to the higher operational burden was to follow the two-tier system which passes on the costs to the PSPs. No mention was made in the paper of the thought that the PSPs will, presumably, seek to recoup these costs through fee structures which would counter the idea that a CBDC might lower payment costs.

54% of the central bans though CBDCs could significantly reduce the cost of cross-border payments, 31% that they would provide some reductions. Cross-border payments do bring some risks.

Despite those concerns, central banks thought that, on balance, limits on access to and usage of cross-border payments could mitigate these risks.

A key element for cross-border interoperability that is gaining attention is the incorporation of digital IDs. Three CBDC models for cross-border interoperability are currently of interest;

The use of a harmonised regulatory frameworks, market practices and messaging formats to ensure compatibility between national retail CBDCs

Linking two domestic systems through technical interfaces (eg. as has been tried in Project Jasper-Ubin)

A single and jointly operated wholesale multi-CBDC system (eg. Project mBridge).

Each of model goes further than the one before in terms of the level of integration they require and imply.

Users would be able to hold CBDCs from various jurisdictions in the CBDC “wallet” of their home jurisdiction, subject to some limits. Cross-border coordination and cooperation are crucial, as stressed by Malaysia.

These models require common governance arrangements, which can be challenging and consistent technical standards, oversight frameworks, and adequate liquidity in several currencies would be necessary. South Africa emphasises several of these considerations based on its experience with a regional RTGS system.

The choices made by large-economy central banks could constrain the options available to smaller countries.

The design areas concerning the central banks were;

1. Interoperability with domestic and cross-border payment systems

2. The degree of central bank involvement

3. Whether interest payments would be needed

4. Limits on transaction amounts, outstanding balances, foreign users and usage abroad by domestic users

5. CBDC-specific data governance policy

6. Underlying technology.

From this list, the design preferences for 1, 2 and 6 were largely understood and agreed. There was uncertainty about 4 and 5 and against 3, CBDCs bearing interest.

Given the importance of financial inclusion to the central banks, survey questions were asked about how the central banks would prioritise designing a CBDC to increase financial inclusion.

The paper concludes with a summary of its key points. The EME central banks largely seek greater payment efficiency but were concerned about achieving financial inclusion and the risks of cyber security, bank disintermediation, and cross-border spill overs. Given each country is unique, particularly around infrastructure, payment competition and data governance, their CBDC design approaches are different. Overall, most EME central banks believe careful design can keep risks to a minimum while still yielding net benefits.

Largely the goal is a “payment-focused CBDC” that does not act as a store of value. This reduces the risk of disintermediation and major monetary policy implications. Again, their design focus does not include paying interest on the CBDCs but does include some limits on balances and transaction values. There is also an inclination to keep the amount of CBDC outstanding small.

To avoid the central bank carrying the burden of operational responsibility, there is a preference for a two-tier system, with the private sector having a major role. Banks are looking to draw on both distributed and central ledger-based network structures. Overall, the central banks seem to be looking for a framework where public and private entities “partner” to create an efficient and stable financial and payment systems.

A view from Latin America - Central Bank of Argentina

Initial steps towards a central bank digital currency by the Central Bank of Brazil - Central Bank of Brazil

The Central Bank of Chile´s approach to retail CBDC - Central Bank of Chile

E-CNY: main objectives, guiding principles and inclusion considerations - People’s Bank of China

Some thoughts about the issuance of a retail CBDC in Colombia - Central Bank of Colombia

Are there relevant reasons to introduce a retail CBDC in the Czech Republic from the perspective of the payment system? - Czech National Bank

Three principles guiding the design of the HKMA’s proposed retail CBDC architecture - Hong Kong Monetary Authority

CBDC – an opportunity to support digital financial inclusion: Digital Student Safe in Hungary - Magyar Nemzeti Bank

CBDCs in emerging market economies - Reserve Bank of India

CBDCs in emerging market economies – a short note - Bank Indonesia

What is an optimal CBDC strategy for small economies? - Bank of Israel

The Bank of Korea's CBDC research: current status and key considerations - Bank of Korea

CBDCs in emerging market economies – Malaysia’s perspective - Central Bank of Malaysia

Policy considerations on CBDCs for emerging market economies - Bank of Mexico

Assessing CBDC potential for developing payment systems and promoting financial inclusion in Peru - Central Reserve Bank of Peru

Deliberations of an emerging market economy central bank on CBDCs - Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas

Evaluation of the rationale for the potential introduction of central bank digital currency in Poland - National Bank of Poland

CBDCs in emerging market economies - Bank of Russia

CBDC and its associated motivations and challenges - Saudi Central Bank

Economic considerations for a retail CBDC in Singapore - Monetary Authority of Singapore

CBDCs in emerging market economies - South African Reserve Bank

Hands-on CBDC experiments and considerations – a view from the Bank of Thailand - Bank of Thailand

View on CBDCs – Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye - Bank of the Republic of Türkiye

CBDCs in emerging market economies - Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates

1 - BIS papers No. 123. ‘CBDCs in emerging market economies.’ Sally Chen, Tirupam Goel, Han Qiu and Ilhyock Shim.