IMF Working Paper: WP/20/254

Authors: Wouter Bossu, Masaru Itatani, Catalina Margulis, Arthur Rossi, Hans Weeink, Akihiro Yoshinaga.

This paper opens asking three questions from a legal perspective,

Do central banks (CBs) have the authority to issue digital currency?

Can Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) be real ‘currency’?

Should digital currency be legal tender?

The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) define a CBDC as being a new form of CB money which is a CB liability, denominated in an existing unit of account and used as a medium of exchange and a store of value. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) use a slightly different definition, describing it as ‘a new form of money, issued digitally by the CB and intended to serve as legal tender.’ The difference between private and CB money is that CB money is a liability on a CB. Liabilities on CB’s are regulated by CB laws.

There are three forms of payment that are referred to in the context of CBDCs and payments.

Currency. This is the official means of payment of a state/monetary union recognised as such by ‘monetary’ laws. Currency is:

Always denominated in the official monetary unit

Legal tender, ie. a debtor can discharge monetary obligations by tendering currency to the creditor

Usually, banknotes and coins

Money. There is no universally accepted legal definition. Currency is usually regarded as money. It often includes other assets or instruments that are readily convertible or redeemable into currency, eg. ‘book money’ - credit balances on account.

Payment instruments. For example, cheques, bills of exchange, promissory notes. These can be legally used to effect payment in commercial banks in book money or currency.

There are four design features to consider, of which the first is the most important.

Account based CBDC (A-CBDC) v Token based CBDC (T-CBDC)

Accounts have a long history, and their legal status is well developed. Tokens are quite new and so their position is unclear.

Wholesale v Retail v General Purpose CBDCs

Wholesale: CBDCs that are used by clearing banks and public bodies have accounts at the CB

Retail: the general public can have accounts at the CB holding CBDCs

General Purpose: CBDCs used by both banks, public bodies and the general public.

Direct (tier 1), Indirect (tier 2) and hybrid CBDCs

Direct CBDCs are issued and administered in circulation by the CB

Indirect (synthetic) CBDCs are issued by commercial banks but fully backed by CB liabilities

Hybrid CBDC are a direct claim on the CB but with intermediaries handling payments.

The liability has to be a direct liability on the CB if the CBDC is to be risk free.

For a T-CBDC, whether and what conditions can it be ‘deposited’ in the books of a commercial bank?

Centralised settlement (as Real Time Gross Settlements today) v decentralised settlement

Decentralised settlement is usually assumed to use Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT). This can be permissioned (you have to ‘ask’ to make a transaction and a record is kept) and permission-less. With the latter, there is the question of how to manage the money supply.

Legally the situation is unclear. One approach to create a working concept is to base this around identity and the requirement to use it to transact. The three different options are,

‘I am therefore I own’ – an account is owned by a known person. Used today for book money and A-CBDCs

‘I possess therefore I own’ – used for physical money and physical tokens

‘I know therefore I own’ –Knowledge of the password allows transfer. Used for digital tokens.

In the taxonomy of CB liabilities, a T-CBDC is neither book money nor a bill. Booking a T-CBDC in a register or ledger operated by a CB is legally not the same as booking of a credit balance in a cash current account. It would require a special provision in CB Law and Monetary Law that is different from the issuance of A-CBDCs.

In a cash current account there is a contractual relationship between the financial institution and the account holder. Legally the financial institution is allowed to lend the account holders money.

In a ledger account, the account is not a contractual concept. The ledger can record assets, liabilities, income and expenses. The ledger is not a legal relationship between reporting entities.

A T-CBDC can be represented in a centrally managed ledger account by the CB, but it is not a credit balance in a current account, and therefore there is no contractual relationship between the CB and the holder of the token.

Central bank law is used to establish the CB, provide for its decision making body, lay foundations for its autonomy and prescribe its mandate. Most CB laws are clear about banknotes and coins, book money (current and reserve accounts) and bills.

The mandate is the key element of this paper. It usually consists of two parts, the CB’s

Functions, its tasks and duties to achieve its objectives. Currency issuance and managing the payment system are usually included in this.

Powers, how the CB can act to implement its functions, eg. to issue certain types of currency, to open specific accounts in the CB books for banks and the state, to support the payment system, to implement monetary policy.

Sometimes the CB’s objectives are included, for example maintaining a stable banking sector.

When the CB law is establishing functions and powers for currency issuance and payments, the key questions are whether the CB law says whether tokens can be issued and if it defines the term ‘currency’? if the issuance power or functions are defined broadly, then the CB may be authorised to issue T-CBDCs.

The law will often refer to specific ancillary powers, for example to design and produce banknotes, or to grant a monopoly of issuance. These may also have implications for issuing CBDCs.

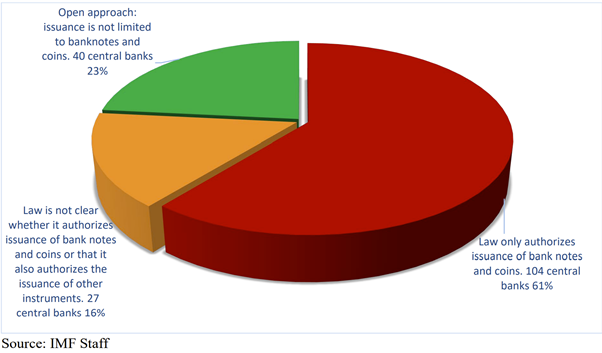

The paper investigated the CB laws of all 171 members of the IMF and found that only 40, 23%, are able to issue CBDCs.

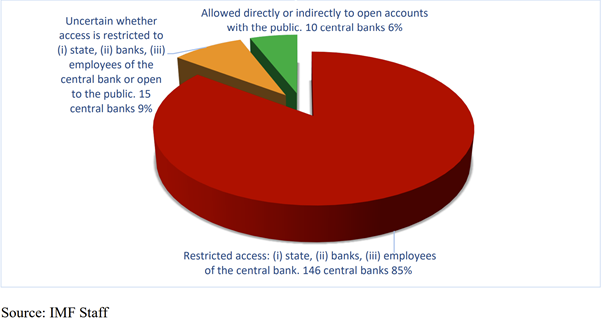

Most CB laws support the issuance of A-CBDCs to financial institutions but often lack the legal basis to issue them to the public. Only 10 central banks, 6%, are allowed to directly or indirectly open CB accounts with the public.

CBs need to consider the legal impact of CBDCs on the payment system function. The definition may be strict, ie. it names specific infrastructure or broad, eg. promote the ’soundness of the national payment system’. At the moment CBs work almost exclusively with interbank payments. A retail CBDC will be between users and may not, therefore, be allowed.

In order to introduce CBDCs, the CB law needs to define the issue of ‘currency’ broadly and to give the CB the power to implement this function specifically including CBDCs.

For A-CBDCs, the law needs to allow CBs to be able to open accounts for the public and to remove any wording that limits the CB to working only with interbank payment systems.

Monetary law is the legislative and regulatory framework that provides the legal foundations for the use of monetary value in society, the economy and the legal system.

In some countries the constitution lays down the basic rules governing the interaction between the state and the monetary system. It:

Allocates the competency to adopt monetary law in federal states to the federal level

Confirms that the issuance of currency is a state matter

Consequently, it regulates what the official monetary unit is and how its value is determined or defined. It also lays down what are the official means of payment.

Is a CBDC a new official monetary unit and/or a new official means of payment?

Based on the answer, what are the CBDCs essential monetary law attributes?

Monetary law today generally lays out the position of currency relative to,

Issuance as a monopoly of the state. Claims on the CB are not all currency, eg. CB book money, CB bills. This is because they are not consistent with Cours Forcé.

Cours Forcé. A current account at the CB can be converted either into banknotes or into CB book money. The value of a banknote is the amount of official monetary unit printed on it.

Legal tender status. The power to validly and definitively extinguish monetary obligations. This is decided by law and is, therefore, a choice. Legal tender can be changed but the paper notes that whatever the change, it must be easily receivable by the vast majority of the population if it is to be ‘fair’.

Privileges under private law.

Criminal law protection. This protects currency against counterfeiting, damage and destruction.

CBDCs are assumed not to be a new currency unit.

If a CB is authorised to issue CBDCs, the CB will digitally issue a liability denominated in the official monetary unit, thereby establishing constant convertibility at par with other CB liabilities.

Is it possible to issue a T-CBDC as an officially sanctioned means of payment?

Issuance by the state. May need to extend the current monopoly working to include digital forms of bearer on demand notes.

Cours Forcé and convertibility. This will need legal definition, assuming physical cash and the token have the same value. In this context a negative interest rate presents a legal challenge since it would break the link between the face value and the actual value of the ‘currency’. How can a T-CBDC extinguish monetary obligations at face value if the real value is different in function of interest? This complicates the convertibility of T-CBDCs in banknote and CB book money. Negative interest rates would not be a legal issue for A-CBDCs.

Legal tender status. This only works if all citizens can receive and use T-CBDCs. If not there will be problems with proportionality, fairness and financial inclusion.

Privileges under private law. This is a highly complex legal area.

Criminal law protection. Current counterfeit rules may not apply.

The papers conclusion is that T-CBDCs are hard to recognise as ‘currency’. Legally they are situated in the taxonomy of CB monetary liabilities between banknotes and coins and bills. They will be able to circulate more widely and be used for payments more than CB bills but not with the same status as banknotes.

Is it possible to issue an A-CBDC as an officially sanctioned means of payment?

Issuance by the state. For wholesale A-CBDCs, yes, since inter-bank settlement accounts already exist. For Retail A-CBDCs, no. CB law would need to be changed to allow them.

Cours Forcé and convertibility. Yes.

Legal tender status. This does not apply to wholesale A-CBDCs since they aren’t used for payments. This is possible for retail A-CBDCs although there may be issues of fairness and public policy if not all citizens can use them. In addition, what happens if creditors cannot accept them?

Privileges under private law. This isn’t applicable although a problem area would be if a creditor wanted to take out an action against a debtors CBDC account at the CB.

Criminal law protection. Considerable work will be need around cyber crime.

The papers conclusion was that an A-CBDC would be difficult but not impossible unless the law is changed.

T-CBDC. The paper saw this as only possible if,

The definition of the users was narrowly and tightly defined to the point where the general public did not use them

There is an assessment if it should be given privileges under private law

If legal cover is in place against cyber crime.

A-CBDC – no changes were recommended

The paper regarded T-CBDC as new because their digital nature is not currently covered in law. A-CBDCs, however, are an extension of existing CB accounts. Their use with the public is not currently covered in law.

Neither is a new monetary unit.

Giving it a legal status will be difficult if it is not usable by most citizens

They have no clear status under private law because it is difficult to extend private law privileges to promote circulation.

Is electronic counterfeiting a legal concept that fits into the broader criminal system? T-CBDCs will need legal protection.

Not actually currency at all. They have the same legal status as other CB book money and therefore no legal reform is needed.